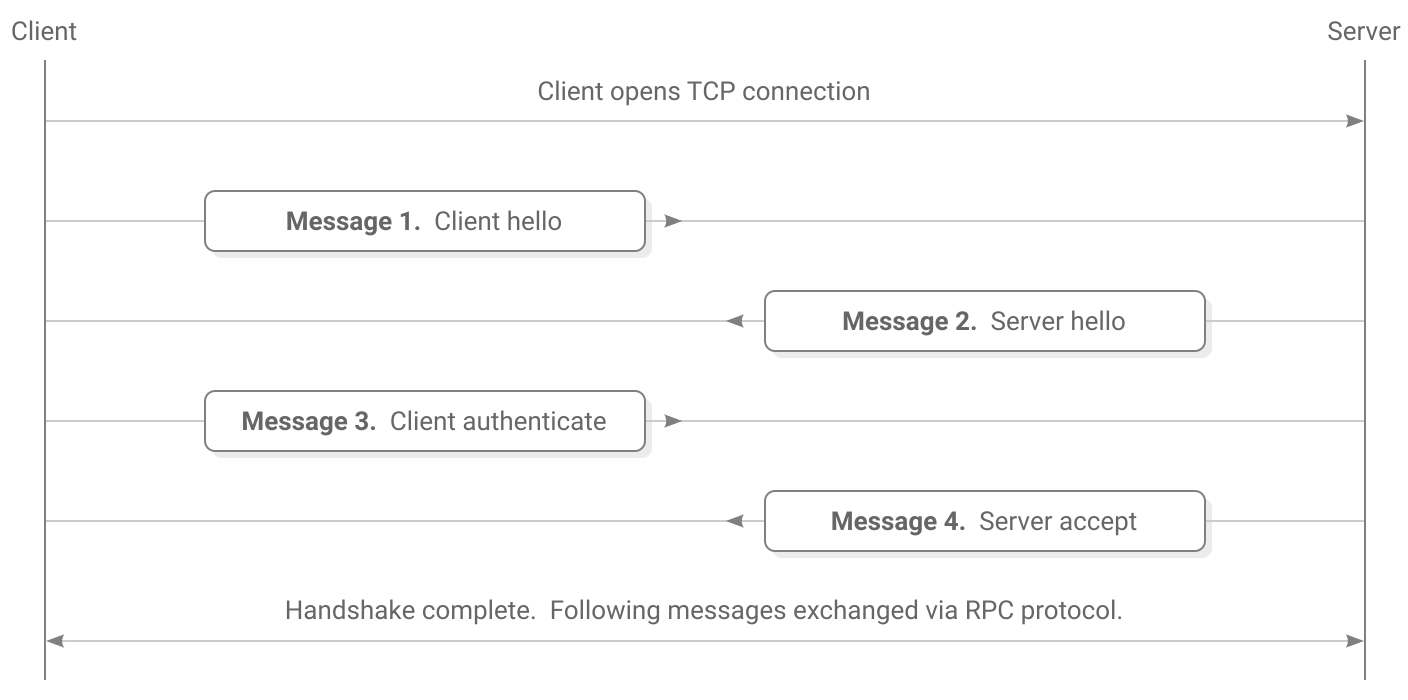

Peer connections

Once a Scuttlebutt client has discovered the IP address, port number and public key of a peer they can connect via TCP to ask for updates and exchange messages.

Handshake

The connection begins with a 4-step handshake to authenticate each peer and set up an encrypted channel.

Implementations

JS:

Python:

Go:

C:

Java:

The handshake uses the Secret Handshake key exchange which is designed to have these security properties:

- After a successful handshake the peers have verified each other’s public keys.

- The handshake produces a shared secret that can be used with a bulk encryption cypher for exchanging further messages.

- The client must know the server’s public key before connecting. The server learns the client’s public key during the handshake.

- Once the client has proven their identity the server can decide they don’t want to talk to this client and disconnect without confirming their own identity.

- A man-in-the-middle cannot learn the public key of either peer.

- Both peers need to know a key that represents the particular Scuttlebutt network they wish to connect to, however a man-in-the-middle can’t learn this key from the handshake. If the handshake succeeds then both ends have confirmed that they wish to use the same network.

- Past handshakes cannot be replayed. Attempting to replay a handshake will not allow an attacker to discover or confirm guesses about the participants’ public keys.

- Handshakes provide forward secrecy. Recording a user’s network traffic and then later stealing their secret key will not allow an attacker to decrypt their past handshakes.

Client is the computer initiating the TCP connection and server is the computer receiving it. Once the handshake is complete this distinction goes away.

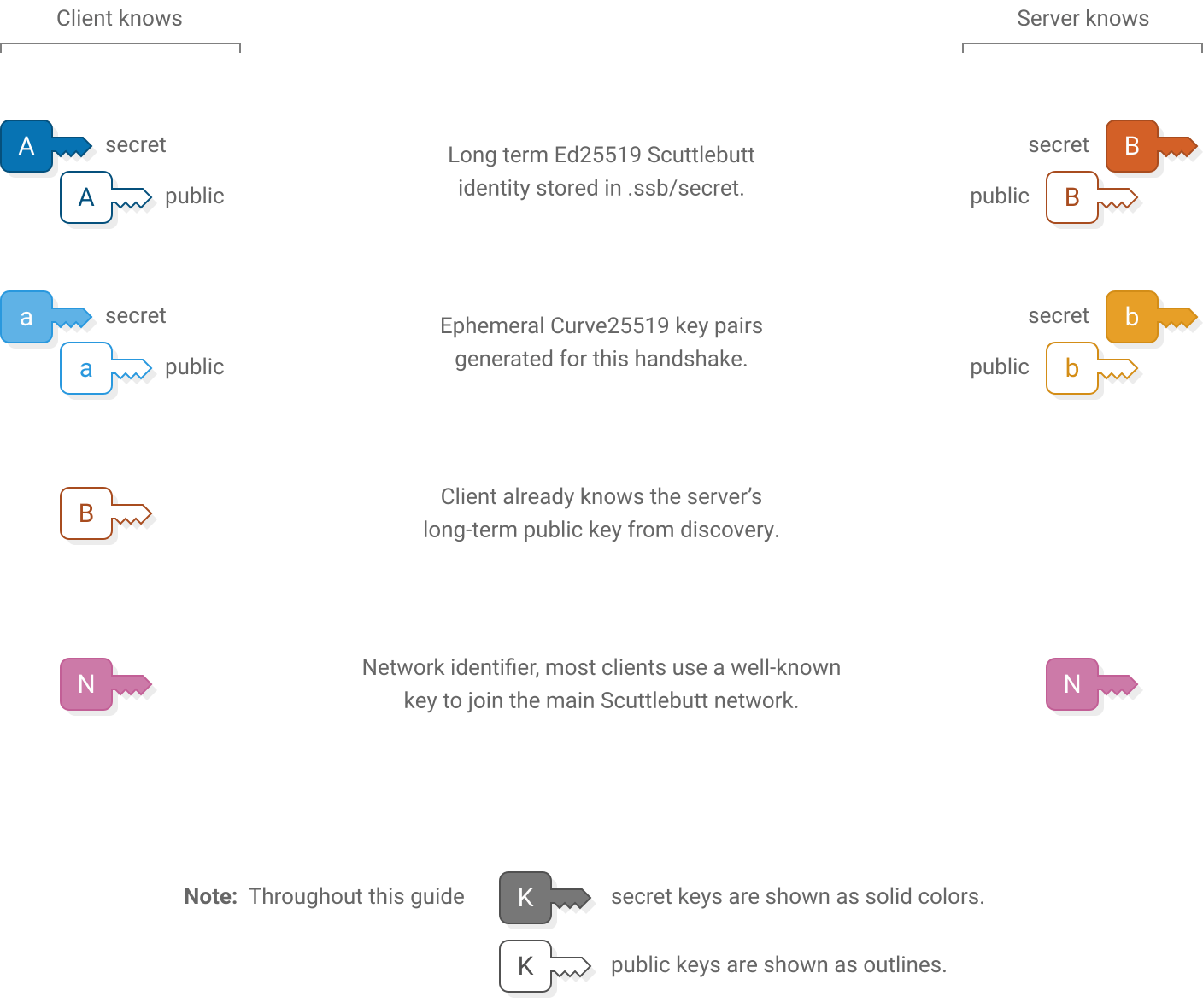

Starting keys

Upon starting the handshake, the client and server know these keys:

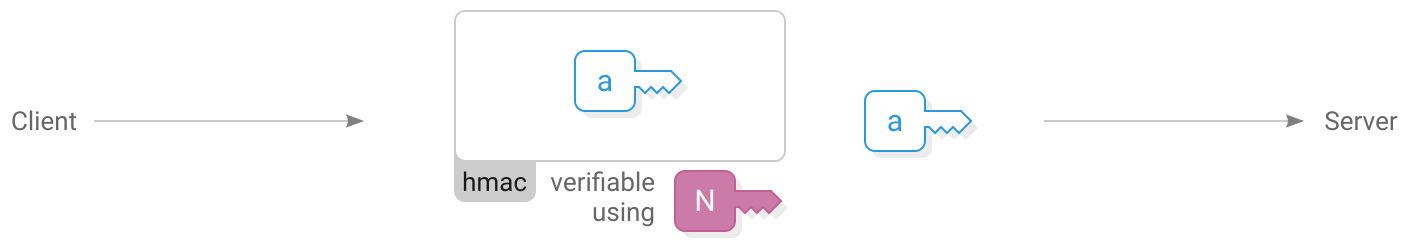

1. Client hello

Client sends (64 bytes)

concat(

nacl_auth(

msg: client_ephemeral_pk,

key: network_identifier

),

client_ephemeral_pk

)Server verifies

assert(length(msg1) == 64)

client_hmac = first_32_bytes(msg1)

client_ephemeral_pk = last_32_bytes(msg1)

assert_nacl_auth_verify(

authenticator: client_hmac,

msg: client_ephemeral_pk,

key: network_identifier

)First the client sends their  generated ephemeral key. Also included is an hmac that indicates the client wishes to use their key with this specific instance of the Scuttlebutt network.

generated ephemeral key. Also included is an hmac that indicates the client wishes to use their key with this specific instance of the Scuttlebutt network.

The  network identifier is a fixed key. On the main Scuttlebutt network it is the following 32-byte sequence:

network identifier is a fixed key. On the main Scuttlebutt network it is the following 32-byte sequence:

| d4 | a1 | cb | 88 | a6 | 6f | 02 | f8 | db | 63 | 5c | e2 | 64 | 41 | cc | 5d |

| ac | 1b | 08 | 42 | 0c | ea | ac | 23 | 08 | 39 | b7 | 55 | 84 | 5a | 9f | fb |

Changing the key allows separate networks to be created, for example private networks or testnets. An eavesdropper cannot extract the network identifier directly from what is sent over the wire, although they could confirm a guess that it is the main Scuttlebutt network because that identifier is publicly known.

The server stores the client’s ephemeral public key and uses the hmac to verify that the client is using the same network identifier.

hmac is a function that allows verifying that a message came from someone who knows the same secret key as you. In this case the network identifier is used as the secret key.

Both the message creator and verifier have to know the same message and secret key for the verification to succeed, but the secret key is not revealed to an eavesdropper.

Throughout the protocol, all instances of hmac use HMAC-SHA-512-256 (which is the first 256 bits of HMAC-SHA-512).

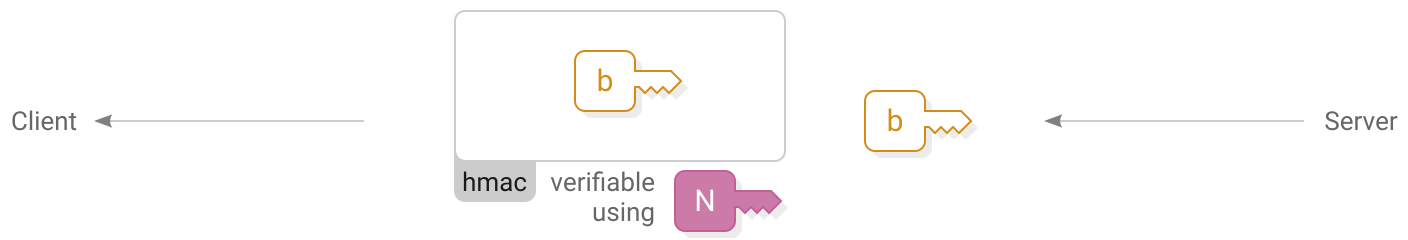

2. Server hello

Client verifies

Server sends (64 bytes)

assert(length(msg2) == 64)

server_hmac = first_32_bytes(msg2)

server_ephemeral_pk = last_32_bytes(msg2)

assert_nacl_auth_verify(

authenticator: server_hmac,

msg: server_ephemeral_pk,

key: network_identifier

)

concat(

nacl_auth(

msg: server_ephemeral_pk,

key: network_identifier

),

server_ephemeral_pk

)The server responds with their own  ephemeral public key and hmac. The client stores the key and verifies that they are also using the same network identifier.

ephemeral public key and hmac. The client stores the key and verifies that they are also using the same network identifier.

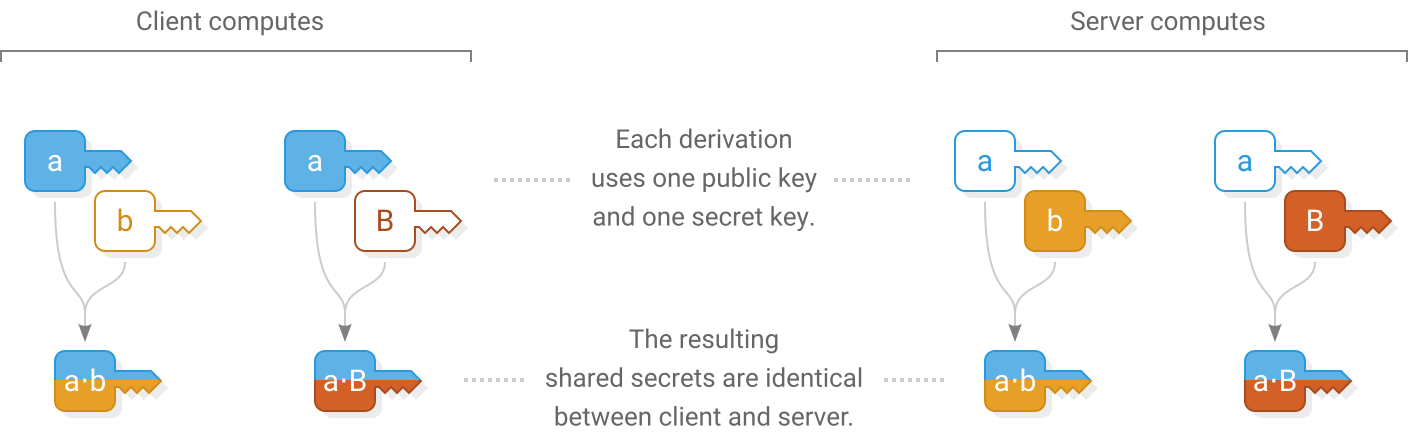

Shared secret derivation

Client computes

Server computes

shared_secret_ab = nacl_scalarmult(

client_ephemeral_sk,

server_ephemeral_pk

)

shared_secret_aB = nacl_scalarmult(

client_ephemeral_sk,

pk_to_curve25519(server_longterm_pk)

)

shared_secret_ab = nacl_scalarmult(

server_ephemeral_sk,

client_ephemeral_pk

)

shared_secret_aB = nacl_scalarmult(

sk_to_curve25519(server_longterm_sk),

client_ephemeral_pk

)Now that ephemeral keys have been exchanged, both ends use them to derive a shared secret  using scalar multiplication.

using scalar multiplication.

The client and server each combine their own ephemeral secret key with the other’s ephemeral public key to produce the same shared secret on both ends. An eavesdropper doesn’t know either secret key so they can’t generate the shared secret. A man-in-the-middle could swap out the ephemeral keys in Messages 1 and 2 for their own keys, so the shared secret  alone is not enough for the client and server to know that they are talking to each other and not a man-in-the-middle.

alone is not enough for the client and server to know that they are talking to each other and not a man-in-the-middle.

Because the client already knows the  server’s long term public key, both ends derive a second secret

server’s long term public key, both ends derive a second secret  that will allow the client to send a message that only the real server can read and not a man-in-the-middle.

that will allow the client to send a message that only the real server can read and not a man-in-the-middle.

Scalar multiplication is a function for deriving shared secrets from a pair of secret and public Curve25519 keys.

The order of arguments matters. In the NaCl API the secret key is provided first.

Note that long term keys are Ed25519 and must first be converted to Curve25519.

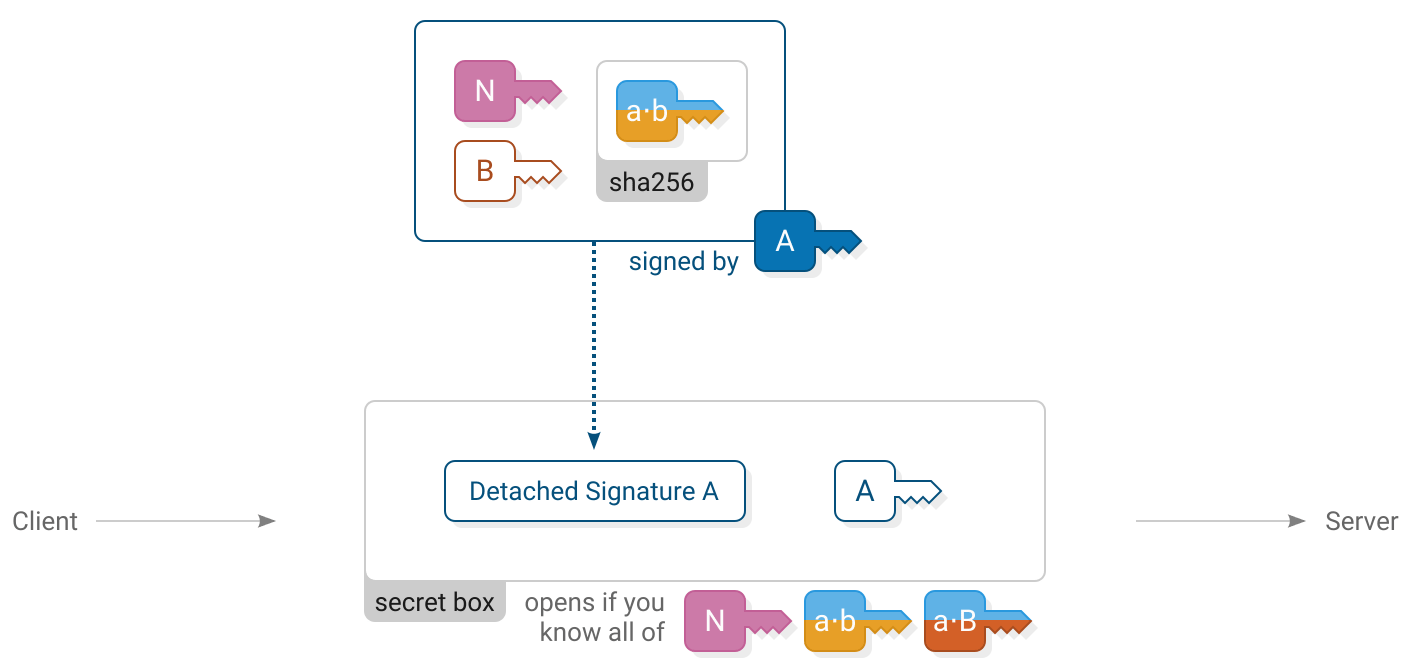

3. Client authenticate

Client computes

Server verifies

detached_signature_A = nacl_sign_detached(

msg: concat(

network_identifier,

server_longterm_pk,

sha256(shared_secret_ab)

),

key: client_longterm_sk

)

msg3_plaintext = assert_nacl_secretbox_open(

ciphertext: msg3,

nonce: 24_bytes_of_zeros,

key: sha256(

concat(

network_identifier,

shared_secret_ab,

shared_secret_aB

)

)

)

assert(length(msg3_plaintext) == 96)

detached_signature_A = first_64_bytes(msg3_plaintext)

client_longterm_pk = last_32_bytes(msg3_plaintext)

assert_nacl_sign_verify_detached(

sig: detached_signature_A,

msg: concat(

network_identifier,

server_longterm_pk,

sha256(shared_secret_ab)

),

key: client_longterm_pk

)Client sends (112 bytes)

nacl_secret_box(

msg: concat(

detached_signature_A,

client_longterm_pk

),

nonce: 24_bytes_of_zeros,

key: sha256(

concat(

network_identifier,

shared_secret_ab,

shared_secret_aB

)

)

)The client reveals their identity to the server by sending their  long term public key. The client also makes a signature using their

long term public key. The client also makes a signature using their  long term secret key. By signing the keys used earlier in the handshake the client proves their identity and confirms that they do indeed wish to be part of this handshake.

long term secret key. By signing the keys used earlier in the handshake the client proves their identity and confirms that they do indeed wish to be part of this handshake.

The client’s message is enclosed in a secret box to ensure that only the server can read it. Upon receiving it, the server opens the box, stores the client’s long term public key and verifies the signature.

An all-zero nonce is used for the secret box. The secret box construction requires that all secret boxes using a particular key must use different nonces. It’s important to get this detail right because reusing a nonce will allow an attacker to recover the key and encrypt or decrypt any secret boxes using that key. Using a zero nonce is allowed here because this is the only secret box that ever uses the key sha256(concat(  ,

,  ,

,  )).

)).

Detached signatures do not contain a copy of the message that was signed, only a tag that allows verifying the signature if you already know the message.

Here it is okay because the server knows all the information needed to reconstruct the message that the client signed.

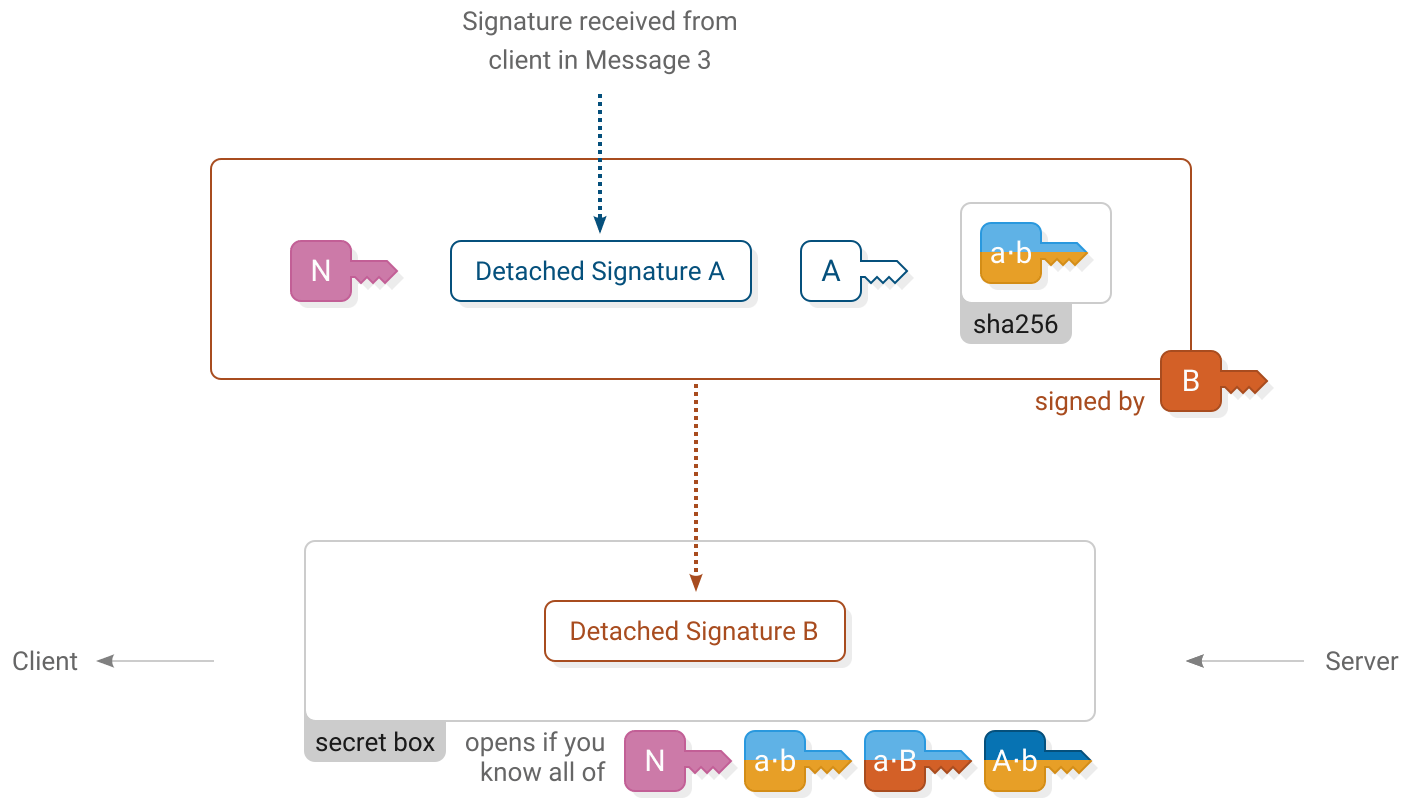

Shared secret derivation

Client computes

Server computes

shared_secret_Ab = nacl_scalarmult(

sk_to_curve25519(client_longterm_sk),

server_ephemeral_pk

)

shared_secret_Ab = nacl_scalarmult(

server_ephemeral_sk,

pk_to_curve25519(client_longterm_pk)

)Now that the server knows the  client’s long term public key, another shared secret

client’s long term public key, another shared secret  is derived by both ends. The server uses this shared secret to send a message that only the real client can read and not a man-in-the-middle.

is derived by both ends. The server uses this shared secret to send a message that only the real client can read and not a man-in-the-middle.

4. Server accept

Client verifies

Server computes

detached_signature_B = assert_nacl_secretbox_open(

ciphertext: msg4,

nonce: 24_bytes_of_zeros,

key: sha256(

concat(

network_identifier,

shared_secret_ab,

shared_secret_aB,

shared_secret_Ab

)

)

)

assert_nacl_sign_verify_detached(

sig: detached_signature_B,

msg: concat(

network_identifier,

detached_signature_A,

client_longterm_pk,

sha256(shared_secret_ab)

),

key: server_longterm_pk

)

detached_signature_B = nacl_sign_detached(

msg: concat(

network_identifier,

detached_signature_A,

client_longterm_pk,

sha256(shared_secret_ab)

),

key: server_longterm_sk

)Server sends (80 bytes)

nacl_secret_box(

msg: detached_signature_B,

nonce: 24_bytes_of_zeros,

key: sha256(

concat(

network_identifier,

shared_secret_ab,

shared_secret_aB,

shared_secret_Ab

)

)

)The server accepts the handshake by signing a message using their  long term secret key. It includes a copy of the client’s previous signature. The server’s signature is enclosed in a secret box using all of the shared secrets.

long term secret key. It includes a copy of the client’s previous signature. The server’s signature is enclosed in a secret box using all of the shared secrets.

Upon receiving it, the client opens the box and verifies the server’s signature.

Similarly to the previous message, this secret box also uses an all-zero nonce because it is the only secret box that ever uses the key sha256(concat(  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  )).

)).

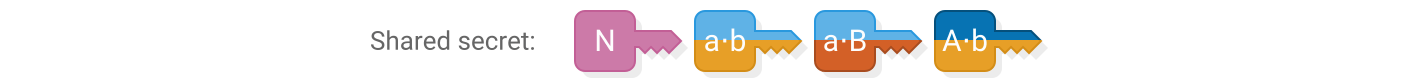

Handshake complete

At this point the handshake has succeeded. The client and server have proven their identities to each other.

The shared secrets established during the handshake are used to set up a pair of box streams for securely exchanging further messages.

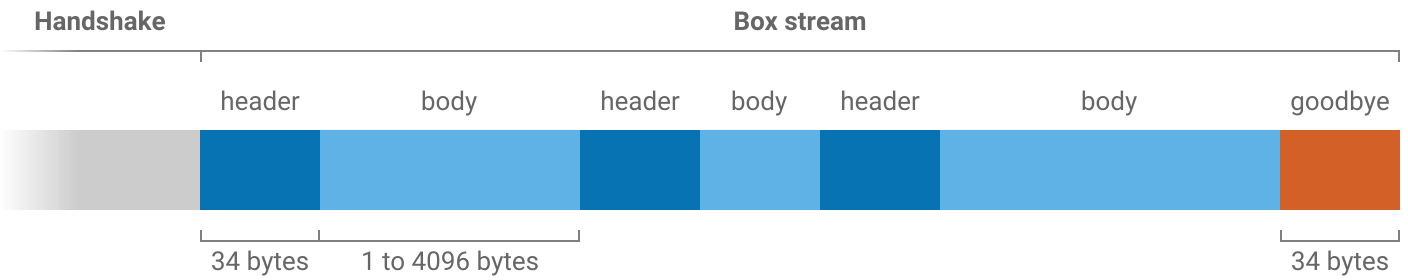

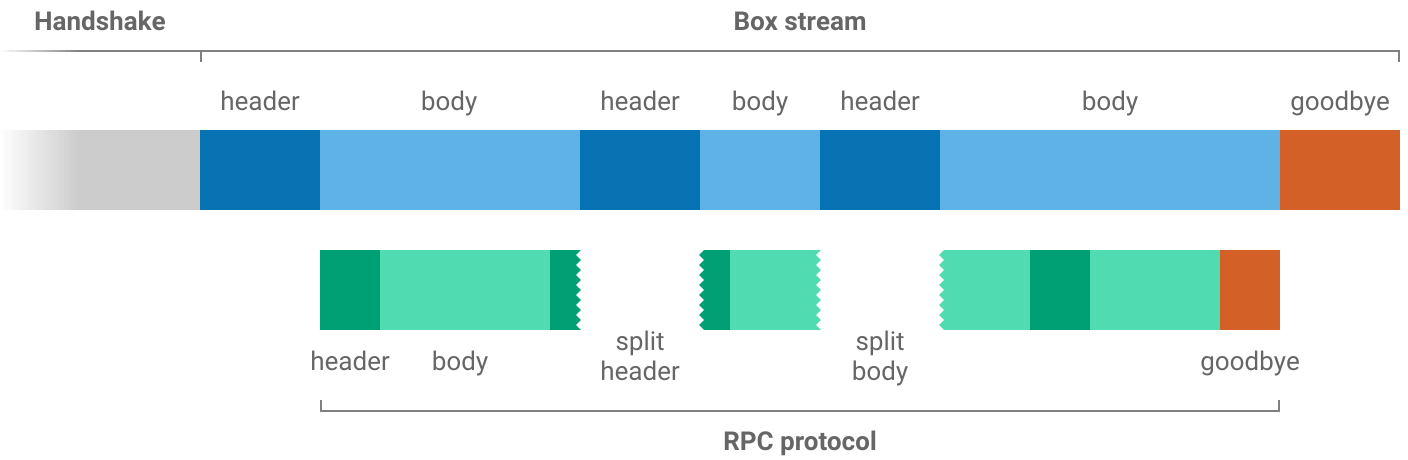

Box stream

Box stream is the bulk encryption protocol used to exchange messages following the handshake until the connection ends. It is designed to protect messages from being read or modified by a man-in-the-middle.

Each message in a box stream has a header and body. The header is always 34 bytes long and says how long the body will be.

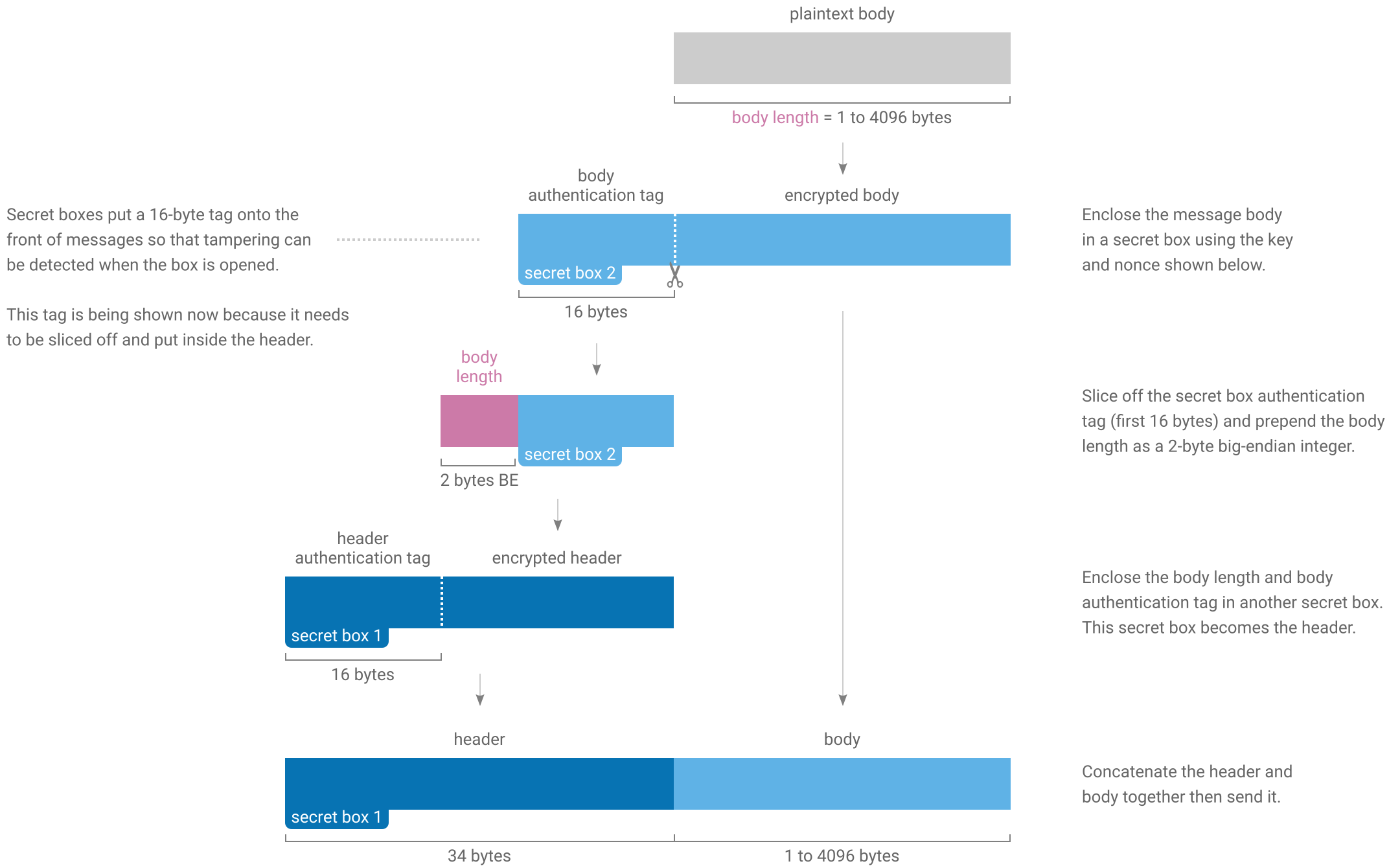

Sending

Sending a message involves encrypting the body of the message and preparing a header for it. Two secret boxes are used; one to protect the header and another to protect the body.

Implementations

JS

Py

Go

C

Java

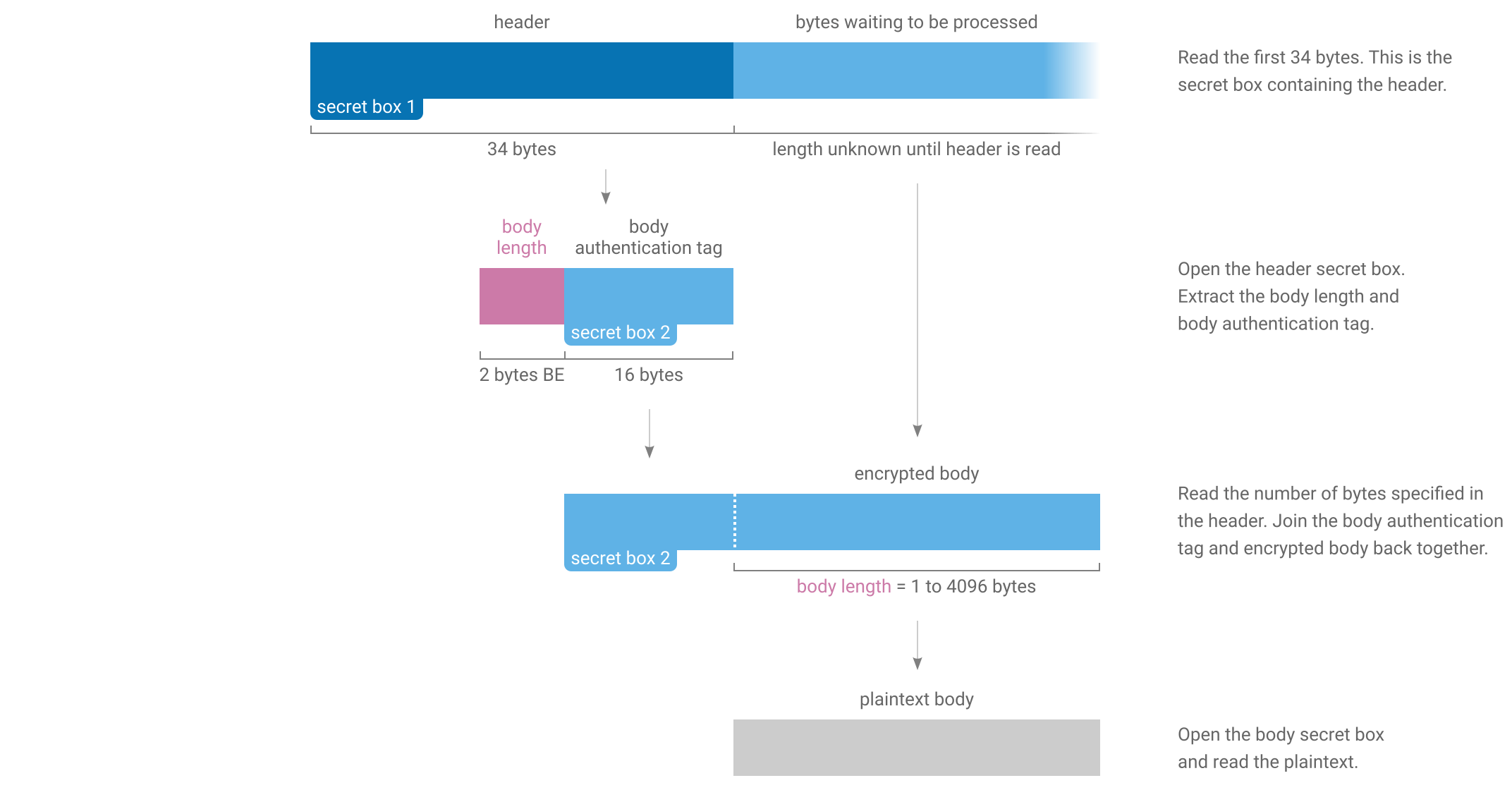

Receiving

Receiving a message involves reading the header to find out how long the body is then reassembling and opening the body secret box.

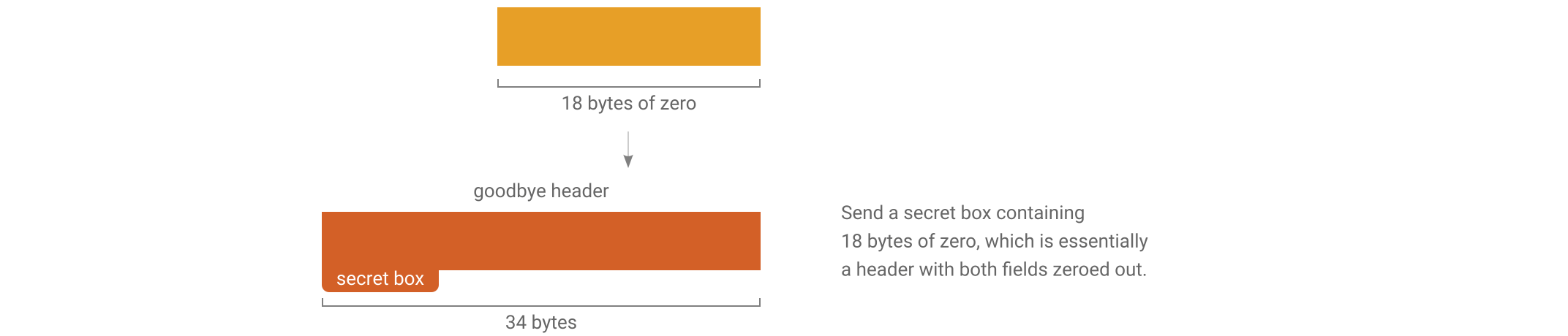

Goodbye

The stream ends with a special “goodbye” header. Because the goodbye header is authenticated it allows a receiver to tell the difference between the connection genuinely being finished and a man-in-the-middle forcibly resetting the underlying TCP connection.

When a receiver opens a header and finds that it contains all zeros then they will know that the connection is finished.

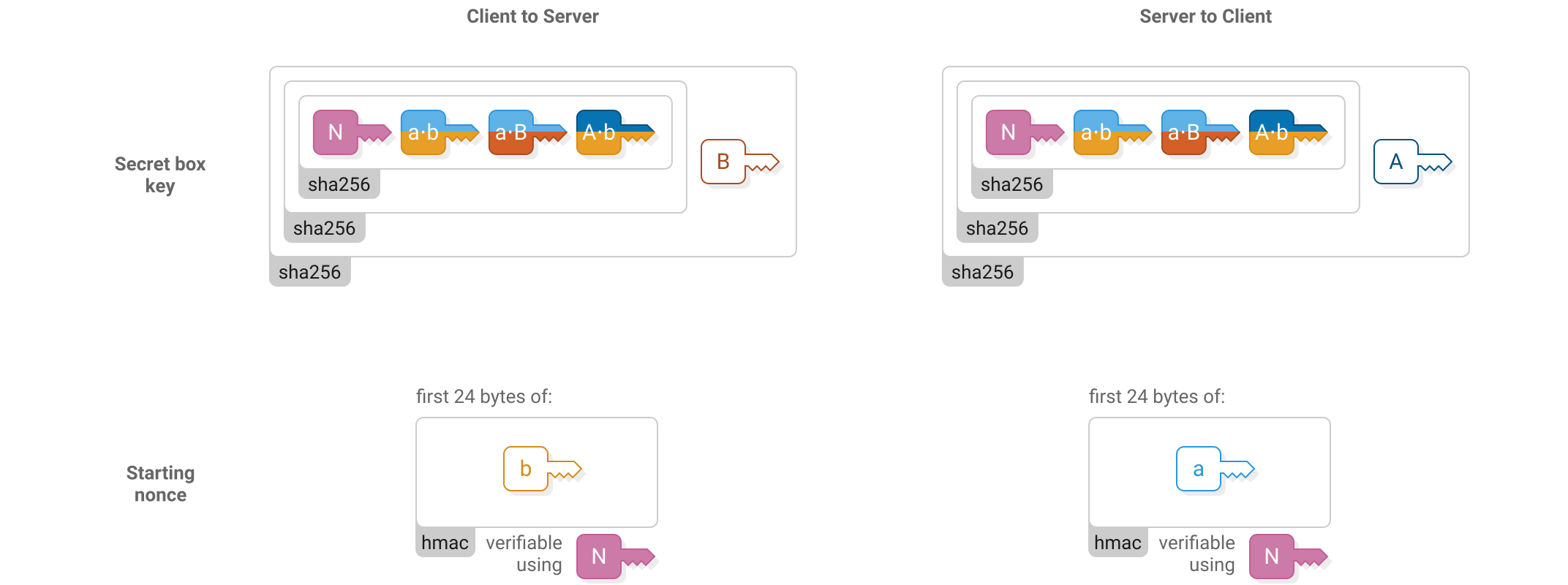

Keys and nonces

Two box streams are used at the same time when Scuttlebutt peers communicate. One is for client-to-server messages and the other is for server-to-client messages. The two streams use different keys and starting nonces for their secret boxes.

The starting nonce is used for the first header in the stream (“secret box 1” in the above figures), then incremented for the first body (“secret box 2”), then incremented for the next header and so on.

RPC protocol

Implementations

JS

Py

Go

C

Java

Scuttlebutt peers make requests to each other using an RPC protocol. Typical requests include asking for the latest messages in a particular feed or requesting a blob.

The RPC protocol can interleave multiple requests so that a slow request doesn’t block following ones. It also handles long-running asynchronous requests for notifying when an event occurs and streams that deliver multiple responses over time.

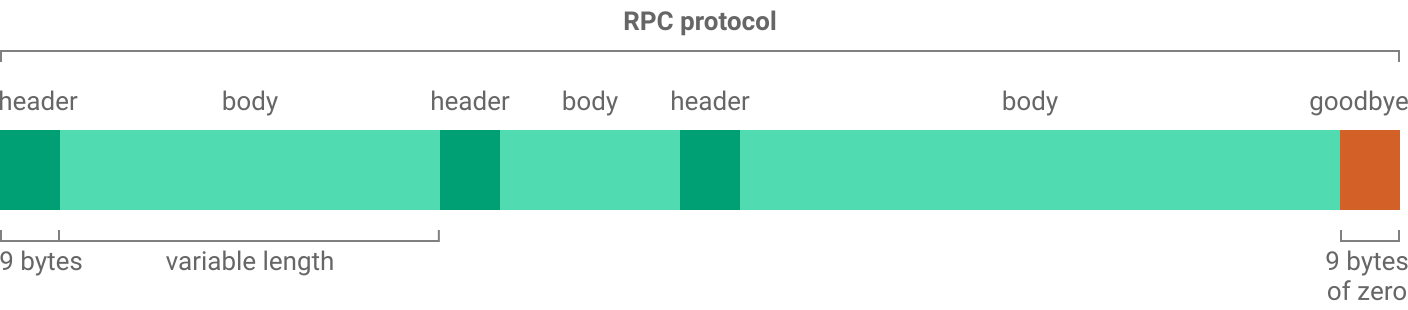

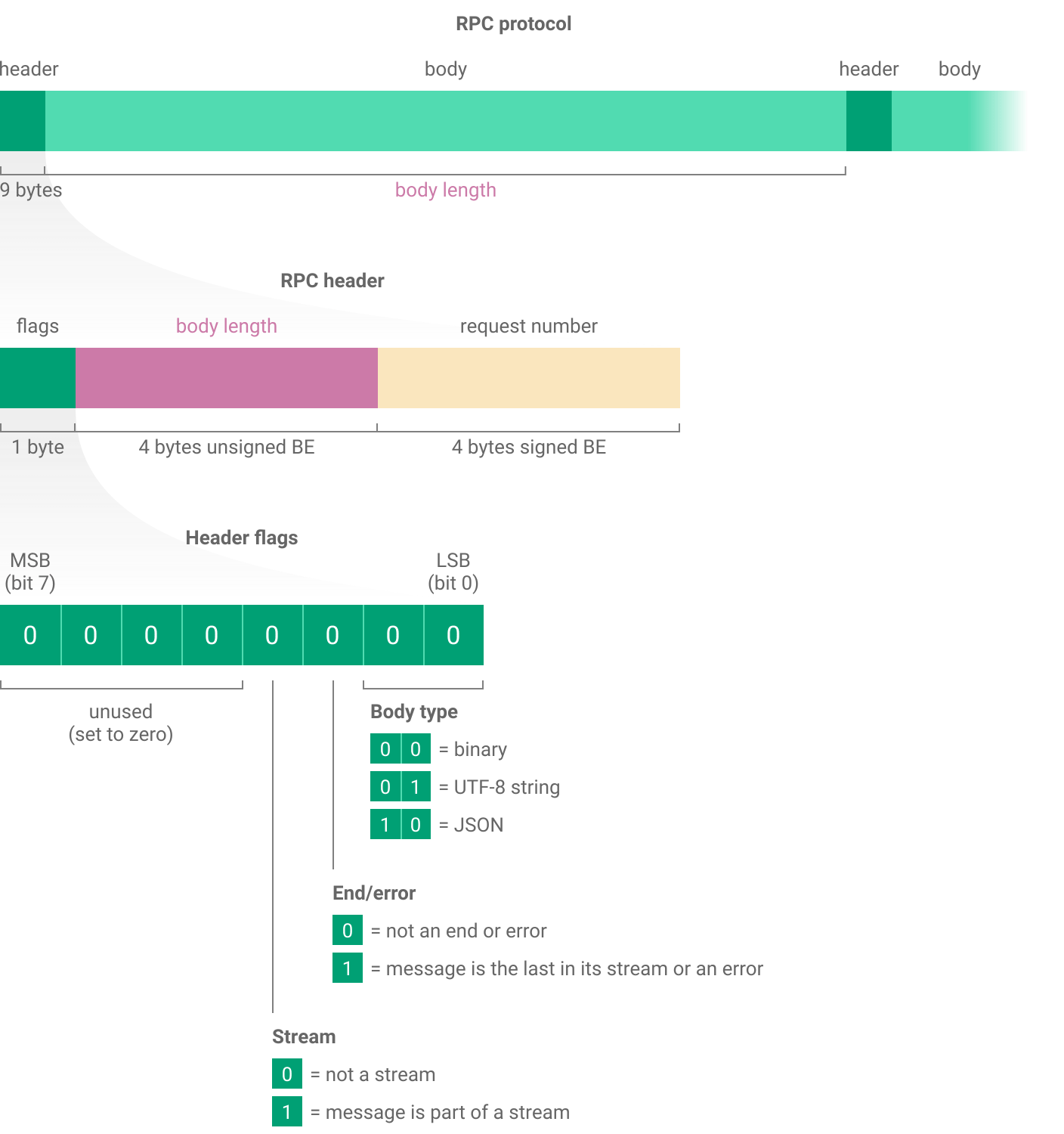

Similar to the box stream protocol, the RPC protocol consists of 9-bytes headers followed by variable-length bodies. There is also a 9-bytes goodbye message which is just a zeroed out header.

Remote procedure calls are where a computer exposes a set of procedures that another computer can call over the network.

The requester tells the responder the name of the procedure they wish to call along with any arguments. The responder performs the action and returns a value back to the requester.

Both peers make requests to each other at the same time using the pair of box streams that have been established. The box streams protect the RPC protocol from eavesdropping and tampering.

RPC messages are not necessarily aligned to box stream boxes.

Multiple RPC messages may be put inside one box or a single RPC message may be split over several boxes.

Header structure

RPC headers contain a set of flags to say what type of message it is, a field specifying its length and a request number which allows matching requests with their responses when there are several active at the same time.

Request format

To make an RPC request, send a JSON message containing the name of the procedure you wish to call, the type of procedure and any arguments.

The name is a list of strings. For a top-level procedure like createHistoryStream the list only has one element: ["createHistoryStream"]. Procedures relating to blobs are grouped in the blobs namespace, for example to use blobs.get send the list: ["blobs", "get"].

There are three types of procedure used when Scuttlebutt peers talk to each other:

- Source procedures return multiple responses over time and are used for streaming data or continually notifying when new events occur. When making one of these requests, the stream flag in the RPC header must be set.

- Duplex procedures are similar to source procedures but allow multiple requests as well as multiple responses over time. The many request events in a duplex utilize the same request number, and the stream flag must be set.

- Async procedures return a single response. Async responses can arrive quickly or arrive much later in response to a one-off event.

For each procedure in the RPC protocol you must already know whether it is source or async and correctly specify this in the request body.

The reference Scuttlebot implementation also has other internal procedures and procedure types which are used by graphical user interfaces like Patchwork.

This guide only covers the procedures that are publicly available to other Scuttlebutt peers.

Source example

This RPC message shows an example of a createHistoryStream request:

JSON messages don’t have indentation or whitespace when sent over the wire.

Request number1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errNo

{

"name": ["createHistoryStream"],

"type": "source",

"args": [{"id": "@FCX/tsDLpubCPKKfIrw4gc+SQkHcaD17s7GI6i/ziWY=.ed25519"}]

}

createHistoryStream is how Scuttlebutt peers ask each other for a list of messages posted by a particular feed. It has one argument that is a JSON dictionary specifying more options about the request. id is the only required option and says which feed you are interested in.

Because this is the first RPC request, the request number is 1. The next request made by this peer will be numbered 2. The other peer will also use request number 1 for their first request, but the peers can tell these apart because they know whether they sent or received each request.

Now the responder begins streaming back responses:

Request number-1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errNo

{

"key": "%XphMUkWQtomKjXQvFGfsGYpt69sgEY7Y4Vou9cEuJho=.sha256",

"value": {

"previous": null,

"author": "@FCX/tsDLpubCPKKfIrw4gc+SQkHcaD17s7GI6i/ziWY=.ed25519",

"sequence": 1,

"timestamp": 1514517067954,

"hash": "sha256",

"content": {

"type": "post",

"text": "This is the first post!"

},

"signature": "QYOR/zU9dxE1aKBaxc3C0DJ4gRyZtlMfPLt+CGJcY73sv5abKK

Kxr1SqhOvnm8TY784VHE8kZHCD8RdzFl1tBA==.sig.ed25519"

},

"timestamp": 1514517067956

}

Request number-1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errNo

{

"key": "%R7lJEkz27lNijPhYNDzYoPjM0Fp+bFWzwX0SmNJB/ZE=.sha256",

"value": {

"previous": "%XphMUkWQtomKjXQvFGfsGYpt69sgEY7Y4Vou9cEuJho=.sha256",

"author": "@FCX/tsDLpubCPKKfIrw4gc+SQkHcaD17s7GI6i/ziWY=.ed25519",

"sequence": 2,

"timestamp": 1514517078157,

"hash": "sha256",

"content": {

"type": "post",

"text": "Second post!"

},

"signature": "z7W1ERg9UYZjNfE72ZwEuJF79khG+eOHWFp6iF+KLuSrw8Lqa6

IousK4cCn9T5qFa8E14GVek4cAMmMbjqDnAg==.sig.ed25519"

},

"timestamp": 1514517078160

}Because the responses are part of a stream, their RPC headers have the stream flag set.

All responses use the same request number as the original request but negative.

Each message posted by the feed is sent back in its own response. This feed only contains two messages.

To close the stream the responder sends an RPC message with both the stream and end/err flags set and a JSON body of true. When the requester sees that the stream is being closed they send a final message to close their own end of it (source type requests must always be closed by both ends).

Request number-1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errYes

trueRequest number1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errYes

true

Alternatively, to abort a stream before it is finished the requester can send their closing message early, at which point the responder closes their own end.

Request number1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errYes

true

Request number-1 Body typeJSON StreamYes End/errYes

trueAsync example

One of the few public async procedures is blobs.has, which peers use to ask each other whether they have a particular blob.

In this example the requester is asking the responder if they have blob &WWw4tQJ6…:

Request number2 Body typeJSON StreamNo End/errNo

{

"name": ["blobs", "has"],

"type": "async",

"args": ["&WWw4tQJ6ZrM7o3gA8lOEAcO4zmyqXqb/3bmIKTLQepo=.sha256"]

}

The responder does in fact have this blob so they respond with true. Because this is an async procedure and not a stream, there is only one response and no need to close the stream afterwards:

Request number-2 Body typeJSON StreamNo End/errNo

trueError example

Let’s take the previous example and introduce a programming mistake to see how the RPC protocol handles errors:

Request number3 Body typeJSON StreamNo End/errNo

{

"name": ["blobs", "has"],

"type": "async",

"args": ["this was a mistake"]

}

Request number-3 Body typeJSON StreamNo End/errYes

{

"name": "Error",

"message": "invalid hash:this was a mistake",

"stack": "…"

}Most importantly, the response has the end/err flag set to indicate that an error occurred. The reference Scuttlebot implementation also includes an error message and a JavaScript stack trace.

For source type procedures an error will also end the stream because the end/err flag has the dual purpose of ending streams and indicating that an error occurred.